The God Who Flew Off With a Mountain

Posted on 25. Jun, 2010 by Paul Sochaczewski in Articles, Curious Travel

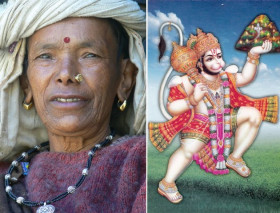

It takes chutzpah for an Indian villager to stay angry at one of the most popular gods in the Hindu pantheon, but Padhan Patti wants her mountain back

DUNAGIRI, India

It takes a bit of Hindu chutzpah for a remote Indian villager to stay angry at one of the most popular gods in the pantheon, but Padhan Patti feels she has a good reason.

“When Lord Hanuman came here to retrieve the medicinal plant mountain he promised to bring it back,” the 50-something woman says, referring to a pivotal scene in the classic Ramayana epic. “But he didn’t.” Padhan Patti promises that when I hike another few hours to a vantage point I will see a huge red scar on the side of Dunagiri Mountain where the flying monkey god Hanuman is said to have sliced off a big chunk of mythological real estate, a scar which “bleeds” in the afternoon sun.

Padhan Patti says she still respects Hanuman, the flying monkey god, because after all he is the Hindu epitome of devotion, selfless courage and good works. Nevertheless, to register her disappointment in his lapse to keep his word she refuses to take the prasad, or communion, at the village’s annual Hanuman festival.

But it’s even more intriguing that Patti’s family, and three other families in this remote, high altitude village of just a few hundred people would bear a grudge for 880,000 years, which, according to some Vedic scholars, is the time when the Ramayana action took place. Obviously we are dealing with several improbables. For a start, 880,000 years ago was some 780,000 years before modern Homo sapiens first stood upright and started their halting journey that led to organized religion. Quite a long time for a cultural memory to persist.

Clearly, Hanuman’s role in the Ramayana is a story for the ages.

Having huge religious and cultural influence, with some of the story lines and poetry of the western Bible, the Odyssey, the Ring Cycle and the search for the Holy Grail, the Ramayana is a hero’s journey involving palace intrigue, broken families, fierce Star Wars-like battles involving a grand collection of deities, ogres and demons, and ultimately the triumph of good over evil. In the story, Prince Rama (an avatar of Vishnu, one of the most powerful Hindu deities) is exiled by his step-mother. Rama, accompanied by his wife Sita and his brother Lakshmana, wander the Indian forests. Sita is kidnapped by the ten-headed demon Ravana, who spirits the woman to his well-protected redoubt in the mythical kingdom of Lanka (located in what is now Sri Lanka). During the numerous battles to rescue Sita, Lakshmana, Rama’s devoted brother, is mortally wounded. The only thing that can save him is sanjivani, a combination of medicinal plants which only grow in the high Himalaya. The royal physician bemoans something like: “But we’re stuck here in Sri Lanka and the plants grow up near the border with Tibet. Who we gonna call?”

This is when Hanuman comes to the rescue. The monkey god flies north some 2,600 kilometers to the medicinal plant mountain, soaring at a speed of roughly 660 km an hour (about 2/3 the speed of a Boeing 747) according to R.P. Goldman, from the University of California at Berkeley, who made his calculation based on the writings of ancient scholars. And then, depending on which of the many versions of the story you read, Hanuman either forgets which plants were on the shopping list or the plants hide in fear when they see this big monkey coming in for a landing. Either way, he rips up the mountain and carries it back to Sri Lanka. After one whiff of the healing herbs Lakshmana is back in business, and Rama and his brother win the final battle, rescue Sita and return to home for a bittersweet finale. In most versions of the story, after the medicines have worked their magic, Hanuman puts the mountain back on his shoulder and flies again over the sub-continent to replace the mountain in its rightful place.

I was exhausted but thrilled as we walked up the steep, narrow path to Dunagiri village. I’ve wanted to find Hanuman’s mountain for some 30 years. Partly it was the quest for something that is inherently “unfindable”, but I was also intrigued by an unintended side benefit. It is difficult to fly over a sub-continent carrying a mountain like a pizza delivery man without bits of it falling to the ground. Where these clumps of medicinal plant dirt fell, sacred forests sprouted. These holy groves, places rich in medicinal plants and generally protected by the local communities, can be found throughout Asia (and indeed throughout the world), and during my work in nature conservation I took a particular interest in their existence and the practical, cultural and spiritual benefits such natural gardens provide to local people. How interesting it would be, I thought, to find the mother lode of these sacred forests.

Some people search for Mount Ararat, where Noah landed. Others seek Atlantis, or Solomon’s temple, or the rumored companion city to Machu Picchu. I was searching for a mythical mountain from a story far older than humanity. But where was it? I read dozens of books, spoke to a gaggle of scholars. Some Ramayana versions give poetically-vague directions — “Go over the sea and north into the far high Himalaya. At night from the air you will easily see the glowing Medicine Hill of Life, crowned with herbs long ago transplanted from the Moon.” Another version of the Ramayana places the medicinal-plant mountain between the (mythical) Rishabha mountain, full of fierce animals, and the (very real) Kailasa mountain, in Tibet. Yet another instructs Hanuman to fly 9,000 yojanas to the red mountain, then another 9,000 yojanas to the blue mountain, and on and on [Indian scholars who calculate such things estimate that one ancient yojana is equal to approximately 13 kilometers to 16 kilometers]. N.C. Shah, of the Central Council for Research in Indian Medicine in Lucknow, pointed me towards Dunagiri by noting that Hanuman’s mountain was located “where kshir, or ocean, was churned for amrita, ambrosia, and where existed two hills, namely Chandra and Drona.” An Indian conservation official said no, the mountain is in his home state of Tamil Nadu, in the south of the country. More prosaically, a friend in Mumbai asked “Why are you interested in this goose chase in the first place? No Starbucks in the mountains.”

Eventually, Ajay Rastogi, a friend in Delhi with whom I had worked during my tenure at the WWF-World Wide Fund for Nature, said that he had heard about a village where some folks refused to share in Hanuman’s communion. Ajay couldn’t make the trip but he introduced me to Gopal Sharma, a tough Indian mountaineer and adventurer. Gopal Sharma had twice summited 7,817 meter Nanda Devi (in one climb he survived a night bivouac without sleeping bag at 7,600 meters, and on another attempt survived a 400 meter fall).

After a comfortable overnight train from Delhi to Haridwar, a holy city where the Ganges leaves the mountains and enters the plains, Gopal and I drove for 12 hours to Joshimath, an Indian hill station in the state of Uttaranchal that suffers from the ugly unregulated construction and traffic of most such resorts. The next morning, driving towards the border with China, we drove another two hours to the trailhead, altitude 2,578 meters, in the general vicinity of the Nanda Devi Sanctuary.

I hike in the Alps on weekends, and am no stranger to the mountains, but I soon tired and huffed and puffed my way to our campsite at Dunagiri village at 3,651 meters.

This was ground zero for my search. The hundred or so villagers in Dunagiri (the village, and the mountain of the same name, are sometimes referred to as Dronagiri) were curious, polite, and after a while quite willing to answer the strange questions of an out-of-breath foreigner. You can’t see the 7,066 meter Dunagiri mountain from the village, and Gopal and I hiked up a few hundred meters to get a good view. We were lucky with the weather (on our departure a few days later it began to snow) and the snow-covered mountain shone like a beacon. We clearly saw the gash where part of the mountain was sliced off. Near our lunch-time picnic spot, in the meadows, we found one of the medicinal plants on Hanuman’s shopping list, visalyakarani, which in Sanskrit means “removing spikes and arrows.” G.S. Rawat of the Wildlife Institute of India subsequently identified the plant as Morina longifolia (Dipsacaceae), used locally to heal wounds.

The search for healing plants in the Himalaya has a basis in fact. Scientists and local people alike know well that the Himalayan region is a treasure chest of important medicinal plants which form the heart of the Ayurvedic system of medicine used to treat Lakshmana, and which remains the medical system of choice for tens of millions of Indians, Nepalese and Sri Lankans .

We returned to the village to say goodbye. I just wanted to be clear that I had the story right, and asked Padhan Patti to confirm that she really was upset with Hanuman because he didn’t return the mountain. She nodded, but added a new fillip, another reason for being perturbed. She told the story with a familiarity and acceptance that was as if she was recounting a family that tale which happened, say, a generation ago, like my father’s war stories. Hanuman flew in during a white-out, she said, and couldn’t find the mountain. Unlike most modern men he stopped to ask directions. The only person in the village was an old woman, an ancestor of Padhan Patti’s. The old woman pointed in the direction Hanuman was to fly. “I can’t see it and I’m in a hurry,” Hanuman replied. So he put her on his shoulder and she navigated while he soared. They arrived, Hanuman said “thanks, have a good life,” grabbed the mountain and flew away, leaving the little old lady alone in the middle of a snow storm.