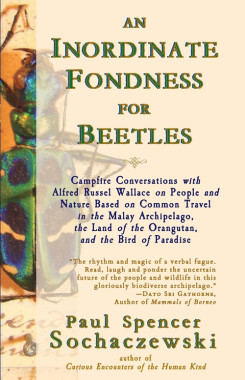

An Inordinate Fondness for Beetles

Posted on 23. Aug, 2012 by Paul Sochaczewski in An Inordinate Fondness for Beetles

An Inordinate Fondness for Beetles

Campfire Conversations with Alfred Russel Wallace on People and Nature Based on Common Travel in the Malay Archipelago,

The Land of the Orangutan and the Bird of Paradise

Explorer’s Eye Press. Geneva. 2017. 454 pages

Second edition April 2017

ISBN 978-2-940573-25-7

Description

While Alfred Russel Wallace is recognized as co-discoverer of the theory of natural selection (and was perhaps deliberately sidelined by Darwin) he was also an edgy social commentator and a voracious collector of “natural productions” – while in Asia he caught, skinned, and pickled 125,660 specimens including 212 new species of birds, 200 new species of ants, and 900 new species of beetles.

In the book Sochaczewski, who has lived and worked in Southeast Asia for more than 40 years, follows Wallace’s eight years of exploration in Southeast Asia, based on Wallace’s classic book The Malay Archipelago.

In An Inordinate Fondness for Beetles Sochaczewski has created an innovative form of storytelling, combining incisive biography and personal travelogue.

Sochaczewski examines important themes about which Wallace (and he) care about deeply — our relationship with other species, humanity’s need to control nature and how this leads to nature destruction, white-brown and brown-brown colonialism, serendipity, passion, mysticism — and interprets these ideas with layers of humor, history, social commentary, and sometimes outrageous personal tales. This is “A new category of non-fiction — part personal travelogue, part incisive biography of Wallace, part unexpected traveller’s tales which coalesce into an illuminating, sometimes bizarre and always-entertaining volume,” according to one reviewer.

Some of the provocative ideas include:

- Why we collect stuff.

- Women’s role in social evolution.

- Orangutan-human communications.

- Passion.

- Brown-brown colonialism.

- Our need/fear relationship with nature.

- Tribal rights.

- Ego.

- Loneliness and aloneness.

- Man as part of nature or man against nature?

- Things that go bump in the night.

- Backyard biodiversity.

Who was Wallace?

Alfred Russel Wallace was a self-taught (he left school at 13) British naturalist, a self-described “beetle collector” who traveled for four years in the Amazon and eight years in Southeast Asia. During his Asian sojourn in the mid-19th century he covered some 22,500 kilometers through territories which are now Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia.

Wallace made his voyages without formal government support, without a floating base camp (like Charles Darwin had with HMS Beagle), without infrastructure, without much cash.

During his epic journey Wallace caught, skinned and pickled 125,660 specimens of “natural productions” including 212 new species of birds, 900 new species of beetles and 200 new species of ants. Consider just the logistics — how could one man, on a tight budget and without organizational support, living rough in rainforests, collect, identify, mount, preserve and transport 8,000 bird skins and 100,000 insects?

If Wallace did nothing more than collect and identify new species he would have left an important scientific legacy. But the breadth of his interests raised him to the top tier of scientists.

His travels through the Indonesian archipelago, supported by his knowledge of geology, helped him develop his understanding of the dynamics of island biology. He observed that the “natural productions” he found in western Indonesia and Peninsular Malaysia were different to those in eastern Indonesia, due to changing sea levels and a combination of shallow seas and deep oceanic trenches. By studying these differences he developed a west-east boundary which came to be known as the “Wallace Line,” the dividing point between (western) Southeast Asian fauna (elephants, tigers, monkeys and apes, hornbills) and fauna of the (eastern) Austro-Malayan realm (kangaroos, birds of paradise, marsupials).

Who was this man? What drove him? Why did he break the cool Victorian mold by writing passionately about finding new butterflies and birds – in one of several similar passages he wrote that he “trembled with excitement” on finding a new species of butterfly. He was both a sentimentalist and a realist — he adopted an infant orangutan after he shot and killed its mother (one of 17 he shot), and then, when the baby animal died, he calmly boiled the animal’s bones in order to obtain a commercially-viable skeleton.

And what led Wallace to develop his contributions to the theory of evolution, first the Sarawak Law (written with the support of the White Rajah of Sarawak, James Brooke), and then the famous Ternate Paper in which he outlined the concept “the fittest shall survive.” Wallace sent the Ternate Paper to Charles Darwin (who up to that point had not published one word on evolution) and at that point the conspiracy theorists get involved. Did Darwin and Wallace arrive at their similar ideas independently? Or did Wallace inadvertently give Darwin the “key” to evolution and subsequently get sidelined by the more prominent and well-placed Darwin?

Reviews

“The feeling I got reading An Inordinate Fondness for Beetles was as if I had boarded a time machine to accompany Wallace as he marveled at and studied the natural wonders of Southeast Asia. The book is a revelation of Wallace’s mesmerizing natural history insights interwoven with Sochaczewski’s unique view of the world and our place in it.”

Thomas E. Lovejoy, professor at George Mason University

“Structures Wallace’s adventures and ideas by themes which resonate with contemporary challenges. Sochaczewski is an explorer of ideas and issues that Wallace cared about deeply: the natural dignity of tribal peoples, the role of colonialism, threats to our natural environment, why boys leave home to seek adventures and collect, how women will determine mankind’s future, and how difficult it is to eliminate ego and greed from people in positions of power.”

Robin Hanbury-Tenison, explorer, author of Mulu: The Rainforest, The Oxford Book of Exploration and The Great Explorers

“I’ve visited many of the places Alfred Russel Wallace and Paul Sochaczewski write about in this exceptional travelogue. An Inordinate Fondness for Beetles does something rare and wonderful – takes us back in time to the mid-19th century when Wallace was collecting and exploring, and forward to the present with insights about Indonesia and our relationship with nature that few people have thought of. This is a true adventure book, it provokes on many levels; it makes me want to dust off my backpack and follow the trail of Wallace once again.”

Aristides Katoppo, editor of Sinar Harapan

“This is a classic hero’s journey – actually a double hero’s journey – which amuses, entertains and surprises us as Wallace and Sochaczewski both experience life-changing adventures in Southeast Asia. Wallace was one of science’s great over-achievers, and by following his trail, Sochaczewski explores, with ample wit and sardonic insight, Wallace’s extraordinary breakthrough in 19th century evolutionary thinking, and reveals how this relates to contemporary Southeast Asian society, politics and the conservation of life on earth.”

Andrew W. Mitchell, founder and director, Global Canopy Programme, and author of The Enchanted Canopy.

“Alfred Russel Wallace isn’t widely known in Indonesia, which is a pity since his passion for the natural world and insights about our relationship with nature (and with each other) contain messages that will help contemporary Indonesians learn how to best respect, protect and manage our vast natural resources. But the book never lectures, never becomes boring. Just the opposite, it is a joy to read, filled with fascinating stories that bring Wallace to life. I intend to insist that my students read this book and consider its messages thoughtfully.”

Jamaluddin Jompa, director of Research and Development Center for Marine, Coasts and Small Islands, Hasanuddin University, Makassar, Indonesia

“A new category of non-fiction — part personal travelogue, part incisive biography of Wallace, part unexpected traveller’s tales which coalesce into an illuminating, sometimes bizarre and always-entertaining volume.”

Jeffrey Sayer, professor of Conservation and Development, James Cook University, founding director general Centre for International Forestry Research-Bogor

“The rhythm and magic of a verbal fugue between two minds, moulded by contrasting background and upbringing; neither man eschews controversy. Read, laugh and, in the light of impacts during the past century and a half, ponder on the uncertain future of the people and wildlife in this gloriously biodiverse archipelago.”

Dato Sri Gathorne, Earl of Cranbrook, author of Mammals of Borneo, Mammals of Southeast Asia, Wonders of the Natural World of Southeast Asia

“Incisive and entertaining, a guidebook for seekers of ideas and people who want a different way of viewing one of the most surprising and dynamic parts of Asia. Wonderfully irreverent.”

Peter Kedit, former director Sarawak Museum (founded by the second White Rajah of Borneo, Charles Brooke, at the suggestion of Alfred Russel Wallace)

“A fascinating journey and dialog with Wallace. Thought-provoking about change and constancy, and a delight to read.”

Peter H. Raven, president emeritus, Missouri Botanical Garden

“This book represents a high point in Sochaczewski’s series of Asian-themed books; he couldn’t have written it without having explored the hidden corners of Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia for 40+ years. It’s simultaneously funny, sardonic, and insightful. Sochaczewski isn’t afraid to shake Wallace’s pedestal once in a while, and doesn’t take himself too seriously either. What I particularly like is its unusual structure – it’s not chronological but thematic – brown-brown colonialism, why boys leave home and collect insects, the joy of solitude, speaking with spirits, how ego stymies nature conservation. The book is like a pizza with everything – Sochaczewski throws in curious facts and anecdotes which enhance the narrative. Reminds me of Bruce Chatwin’s Songlines and Redmond O’Hanlon’s Into the Heart of Borneo. I think he might even have created a new genre – part biography, part travel adventure, part commentary, part something new and refreshing.”

Jim Thorsell. Senior advisor on World Heritage to IUCN

“Wallace, the unsung co-discoverer of evolution, is brought to life in a new and informative way.”

Sir Ghillean Prance, former president the Linnean Society, former director Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

“A natural storyteller, Paul Sochaczewski has created something much bigger than an “in the footsteps of” book. He has produced a work that looks at the themes Wallace wrote about and lived through — women’s power, why boys leave home, the need to collect, our relation with other species, nature destruction, arrogance, the role of ego, white-brown and brown-brown colonialism, serendipity, passion, mysticism — and interpreted them through his own filter. He is a gifted storyteller and the layers of thought, humor, history, commentary and outrageousness Sochaczewski has given us provides a very special view of Wallace that goes beyond biography, beyond travelogue, beyond memoir.”

Daniel Navid, international environment and development law expert, former UN diplomat and founding secretary general of the International Wetlands Convention

“Many of us dream about how exciting it must have been back in the days when Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace were discovering new ways to think about life. Paul Sochaczewski has shown us that the dreams can go live, if one just heads out and looks for the kinds of intriguing, bizarre, exciting, and mind-bending stories that he writes so well. As Wallace might have said, “diversity is the spice of life,” and Paul’s adventures with Wallace will make your mental curry taste like a party in your brain.”

Jeffrey McNeely, chief scientist, IUCN-International Union for Conservation of Nature

“We all owe Wallace a great debt of gratitude for helping us to understand how biological diversity resonates with and is inseparable from cultural diversity, something anthropologists and others are only recently documenting systematically. Likewise we are greatly indebted to Sochaczewski for adding his own observations and insights about how the human relationship with nature is changing in ways that Wallace suggested might occur. It’s rare to find such a captivating book like this one which so creatively combines hard science, passion, whimsy and travel adventures of a very special kind.”

Leslie E. Sponsel, author, Spiritual Ecology: A Quiet Revolution

“One of the best books about Alfred Russel Wallace’s adventures, insights and impact, coupled with Sochaczewski’s tales of modern mysticism, corruption, arrogance, courage, greed and inspiration in Southeast Asia. All combined in a startlingly innovative literary form that I’ve never come across previously.

John G. Wilson, author of The Forgotten Naturalist: In Search of Alfred Russel Wallace

“After suffering years of neglect, the life and times of Alfred Russel Wallace – the “Grand Old Man of Science” – have been enjoying somewhat of a revival over the last decade or so. But lest one is tempted to think that Paul Sochaczewski has written yet another book on Wallace, take a peek inside, sense the ‘campfire conversations’, read a chapter, and then start at the beginning and enjoy the whole book. Sochaczewski takes us not on a chronological or geographic adventure with Wallace, but on a much more thoughtful journey in which Wallace himself is explored through his writings, compared and shared by Sochaczewski‘s own travels and experiences (by turn fun, weird, and somber) in many of the same places Wallace knew. Many of us who have read Wallace and have seen his specimens will discover much here, not just about him, but also perhaps, ourselves.”

Tony Whitten, Asia director for Fauna & Flora International, author of various Ecology of Indonesia volumes

“A classic hero’s journey that amuses, entertains and surprises us as Wallace and Sochaczewski experience life-changing moments in their travels through Southeast Asia. Working on several fronts as a coming-of-age book, a travelogue, a bonding of minds, and a good page-turning yarn, the book is compelling with enlightening insights woven in an engrossing narrative.”

Mo Tejani, author of Global Crossroads: Memoirs of a Travel Junkie

“A modern-day adventurer in his own right, Sochaczewski retraces the physical and intellectual journey of Alfred Russel Wallace, the great explorer, naturalist, humanist and pioneering theoretician on evolution by natural selection. The reader, in turn, is swept along on a quest to discover the dynamics that shape our natural world. In a virtual dialogue, both explorers bring their individual experiences to bear.”

Javed Ahmad, former director of Communication, Environmental Education and Publications of the World Conservation Union-IUCN

“A fascinating exploration of the people and places that touched Wallace, and insights into his mind seen through the author’s personal journey retracing those epic journeys. A deeply personal telling of Southeast Asia’s character and nature, through the eyes of a naturalist, and a traveler. An enticing read.”

Tony Sebastian, past president of the, Malaysian Nature Society, president Friends of Sarawak Museum

“This is an audacious book in which Paul Sochaczewski talks with Alfred Russel Wallace, bridging 150 years of change in ecology, geography and demographics. Sochaczewski entertainingly discusses Wallace’s views on the natural history of the Malay Archipelago side-by-side with his own reflections on contemporary 21st- century Southeast Asia.”

Natarajan Ishwaran, director of ecological and earth sciences at, director of Ecological and Earth Sciences, UNESCO

“This is a Really Good Book! Paul Sochaczewski has written a scholarly personal travel book that is much, much more. He follows Alfred Russel Wallace to little-visited corners of Asia, discussing Wallace’s views and discoveries combined with the author’s erudite insights and musings into history, philosophy, people, and natural history. Extremely well written with nice touches of humor, this book is hard to put down. “

Lee M. Talbot, professor of Environmental Science and Policy, George Mason University; former director general, IUCN, environmental adviser to three United States presidents.

Sample chapter (excerpt)

THE SEARCH FOR ALI

Borneo lad takes part in momentous discovery; then is totally ignored.

Kuching, Sarawak, Malaysia

The Borneo newspapers in 1858 sported a large headline: “Local Borneo lad helps develop theory of evolution.”

The local reporters told how a teen-aged cook from Sarawak named Ali assisted Alfred Russel Wallace on his eight-year adventure in Southeast Asia, culminating in Wallace’s development of the Theory of Natural Selection.

The Borneo newspapers revealed how Ali nursed Wallace during a malaria fever, giving the older Englishman strength and moral support to write the theory that changed the way we view ourselves and our place in the scheme of things.

The Borneo newspapers, of course, said none of these things. Ali was then, and remained, a footnote, an historical afterthought written in small type.

* * *

I have many quests.

I seek tiger magicians in Sumatra. Snowmen of the Jungle in Flores. I seek reasons why people believe in the power of magic amulets and oceanic mermaids and white elephants. I seek the secrets of growing healthy, juicy tomatoes. I seek a writing voice that makes people sit up and take notice — I don’t expect them to leap and shout “huzah!” but a satisfied smile once in a while would be welcome. I seek someone who can explain the Higgs boson. I seek the answer to why some people believe in a stern Hairy Thunderer while other people bow to a benign Cosmic Muffin while other people value spirits in the trees and waterfalls and other folks consult astrological charts and brightly designed tarot cards and yet other people scoff at metaphysics and choose to rely on their own judgment and inner values.

And I have spent forty years trying to find out more about Ali. Who he was, why he went with Wallace, what his contribution was, and where he ultimately settled.

It’s been a lonely quest.

* * *

Western history treats famous explorers as individuals who braved the elements alone, stoic, unflappable and with immense strength of character and fortitude. But actually, all explorers, the famous as well as the over-looked, relied on often-unheralded people to assist in their odyssey. Lewis and Clark had Sacagawea, Edmund Hillary had Tenzing Norgay. Ferdinand Magellan had Enrique, a slave he bought in Malacca and whom he encouraged (I use the term advisedly) to renounce Islam and convert to Catholicism. Enrique became Magellan’s interpreter, guide and assistant; he may also have been among the first people to complete the circumnavigation of the globe, since Magellan, who gets the credit, was killed in the Philippines before finishing the epic journey while Enrique might have continued the voyage to its conclusion.

British naturalist and explorer Alfred Russel Wallace had Ali, and without Ali’s assistance it is unlikely Wallace would have been as successful as he was.

That’s about all we know.

* * *

Alfred Russel Wallace had only been in the Malay Archipelago for just six months (previously he was in Malacca and Singapore) when he went to Sarawak, at the invitation of James Brooke, the famed “White Rajah” of Sarawak.

Wallace was enthusiastic and bright. But he was new to Southeast Asia. He knew just a few words of Malay, the lingua franca of the region. Yes, his Amazon experience helped him immensely in surviving in alien environments and cultures. Yet in Asia he was a stranger in a strange land.

Wallace engaged Ali in late 1855.

Ali accompanied Wallace on most of his subsequent Asian travels. Starting out as a cook, Ali learned to collect and mount specimens. He took on more responsibility for organizing travel (just imagine the negotiations with self-important village chiefs, unreliable porters and laborers, and greedy merchants, whose eyes no doubt grew large when they saw a white man like Alfred come to buy supplies). Ali became an invaluable asset; Wallace called him “my faithful companion.”

* * *

There’s an awful lot we don’t know about Ali. Where he came from. How Wallace met him, and under what terms. Whether he went to school. Where he settled when he parted ways with Wallace. And most interesting, what did Ali think of the awkward, bearded Englishman who spent his days collecting innumerable insects and his nights writing in a small notebook by the dim light of an oil lamp.

* * *

Christopher Vogler is a Hollywood screenwriter whose book The Writer’s Journey explores how a classical mythic structure is used in popular films such as Casablanca, The Wizard of Oz, Star Wars, and Close Encounters of the Third Kind. “All stories consist of a few common structural elements found universally in myths, fairy tales, dreams, and movies,” Vogler says. “They are known collectively as The Hero’s Journey.”

One essential archetype in the hero’s journey is the character Vogler calls the Mentor (and which philosopher Joseph Campbell refers to as the Wise Old Man or the Wise Old Woman), who teaches and protects heroes and gives them gifts. In classical mythology as well as contemporary novels, the Mentor is a sage adult – Merlin guiding King Arthur, the Fairy Godmother helping Cinderella, or a veteran sergeant giving advice to a rookie cop.

If you wish to plot Ali’s hero’s journey in this way, then Wallace was clearly the Mentor, and Ali took the role of a keen, but initially naïve, son who grows in competence and confidence as the story progresses. We can assume that when Wallace met Ali, the Malay teenager had never left Sarawak, probably had never had a serious conversation with a European, and had a limited worldview. Wallace took him on a magnificent journey lasting almost eight years, and by the time Ali and Wallace parted company, Ali no doubt had grown considerably.

“Ali would have been one of the most widely traveled Malays of his age,” according to Gerrell Drawhorn of California State University, Sacramento. “He would have seen most of what is today modern Indonesia (Papua to Sumatra). He would have seen the ancient Hindu temples of Java; the modern metropolises of Batavia and Singapore; the primitive villages of the people of Dorey and the stylized royal courts of central Java. He tasted modern science and medicine and yet retained his beliefs in ghosts and men who could transform into tigers.”

* * *

The reverse is also true.

Yet just as Wallace taught and guided Ali through new adventures, perspectives and skills, Ali was similarly Wallace’s guide. The Englishman was a good pupil and Wallace’s steep learning curve, abetted by Ali, included mastering the Malay language, understanding the vagaries of dozens of cultural groups (Wallace compiled some fifty-seven vocabularies during his travels in Asia), and becoming comfortable with an Asian world view in which ghosts, tiger magicians, birds and kings danced an intricate waltz of cohabitation.

* * *

Under what circumstances did Wallace hire Ali? My theory:

Wallace formed a friendship with Rajah James Brooke and Brooke’s secretary and friend Spenser St. John, and they enjoyed many evenings in wide-ranging discussion. I figure that one night, over brandy, James Brooke said: “Look here Wallace, here in Sarawak people know you’re my friend and they will tolerate your curious behavior and listen to your baby-talk Malay and won’t cheat you too much. But out there [no doubt he was pointing south to the maze of countless Indonesian islands where Wallace was heading] they’re going to eat you alive.” Brooke then asked one of his Malay assistants if he had a young relative who would be willing to go off on an adventure from which he might not return. The result was the Ali-Wallace partnership.

Here’s how Wallace described his engagement of Ali as personal assistant:

When I was at Sarawak in 1855 I engaged a Malay boy named Ali as a personal servant, and also to help me to learn the Malay language…. He was attentive and clean, and could cook very well.[1]

Wallace described how Ali grew into the job, growing from cook to collector to preparer of specimens to manager of a often-changing team of laborers, hunters and boat crews — more than one hundred men worked for Wallace in the Malay Archipelago.

He soon learnt to shoot birds, to skin them properly, and latterly even to put up the skins very neatly. Of course he was a good boatman, as are all Malays…. He accompanied me through all my travels, sometimes alone, but more frequently with several others, and was then very useful in teaching them their duties, as he soon became well acquainted with my wants and habits.[2]

Wallace made no secret of the fact that quite a few of the 125,660 specimens he obtained in the Malay Archipelago were collected by his various collecting assistants (perhaps some thirty men), including an English assistant named Charles Allen. Earl of Cranbrook and Adrian G. Marshall, in a 2014 article in The Sarawak Museum Journal, note that Wallace regularly “bought trade specimens [and] was always ready to recruit casual help in collecting, whether small boys with blowpipes or local hunters and bird traders.”

Yet it was Ali who saw himself as the senior collector, taking great pride in his work and collecting a bird that became one of Wallace’s most-prized specimens:

Just as I got home I overtook Ali returning from shooting with some birds hanging from his belt. He seemed much pleased, and said, ‘Look here, sir, what a curious bird!’ holding out what at first completely puzzled me. I saw a bird with a mass of splendid green feathers on its breast, elongated into two glittering tufts; but what I could not understand was a pair of long white feathers, which stuck straight out from each shoulder. Ali assured me that the bird stuck them out this way itself when fluttering its wings, and that they had remained so without his touching them. I now saw that I had got a great prize, no less than a completely new form of the bird of paradise, different and most remarkable from every other known bird…. This striking novelty has been named by Mr. G.R. Gray of the British Museum, Semioptera Wallacei [today it’s known as Semioptera wallacii], or ‘Wallace’s Standard-wing.’[3],[4]

Ali was so proficient that he might have been responsible for collecting a large number of Wallace’s total of 8,050 bird specimens, which included 212 new bird species.

Within a year of hiring him Wallace described Ali as “my head man”:

Ali, the Malay boy whom I had picked up in Borneo, was my head man. He had already been with me a year, could turn his hand to any thing, and was quite attentive and trustworthy. He was a good shot, and fond of shooting, and I had taught him to skin birds very well.[5]

And Wallace eventually trusted Ali to go by himself to buy specimens. Note that Ali was ill (poor health dogged both Ali and Wallace throughout the journey) and that he was trustworthy and respected by outsiders:

My boy Ali returned from Wanumbai, where I had sent him alone for a fortnight to buy Paradise birds and prepare the skins; he brought me sixteen glorious specimens, and had he not been very ill with fever and ague might have obtained twice the number. He had lived with the people whose house I had occupied, and it is a proof of their goodness, if fairly treated, that although he took with him a quantity of silver dollars to pay for the birds they caught, no attempt was made to rob him, which might have been done with the most perfect impunity. He was kindly treated when ill, and was brought back to me with the balance of the dollars he had not spent.[6]

Ali showed that he had pride in his work; it was more than a job — he seemed to enjoy his role as a trusted bird collector and was willing to endure pain and discomfort to obtain a rare creature.

Soon after we had arrived at Waypoti, Ali had seen a beautiful little bird of the genus Pitta, which I was very anxious to obtain, as in almost every island the species are different, and none were yet known from Bouru [now Buru]. He and my other hunter continued to see it two or three times a week, and to hear its peculiar note much oftener, but could never get a specimen, owing to its always frequenting the most dense thorny thickets, where only hasty glimpses of it could be obtained, and at so short a distance that it would be difficult to avoid blowing the bird to pieces. Ali was very much annoyed that he could not get a specimen of this bird, in going after which he had already severely wounded his feet with thorns; and when we had only two days more to stay, he went of his own accord one evening to sleep at a little hut in the forest some miles off, in order to have a last try for it at daybreak, when many birds come out to feed, and are very intent on their morning meal. The next evening he brought me home two specimens, one with the head blown completely off, and otherwise too much injured to preserve, the other in very good order, and which I at once saw to be a new species, very like the Pitta celebensis, but ornamented with a square patch of bright red on the nape of the neck. [italics added][7]

And in due course Wallace trusted Ali to scout locations that might be sufficiently productive for Wallace to go to the expense and trouble of moving his camp.

It became evident, therefore, that I must leave Cajeli [on Buru] for some better collecting-ground … I sent my boy Ali … to explore and report on the capabilities of the district [Pelah]…. [after an account of a difficult walk that occupies two pages of text Wallace continues] I waited Ali’s return to decide on my future movements. He came the following day, and gave a very bad account of Pelah, where he had been.[8] [italics added]

* * *

I don’t want to overstate his involvement, since his role was supportive rather than intellectual, but Ali was present when Wallace made his most important scientific breakthroughs in his quest to understand and prove evolution.

Ali was not present in February 1855 when Wallace wrote his Sarawak Law (“On the Law which has Regulated the Introduction of New Species”). This paper, published in September 1855, was an important first step towards Wallace’s Theory of Natural Selection and includes the statement “Every species has come into existence coincident both in space and time with a pre-existing closely allied species.”

Ali did, however, play a role in Wallace’s second breakthrough, which came three years after the Sarawak Law.

Wallace wrote that, while in Ternate in eastern Indonesia in February 1858, Ali cared for him during the periods when he was “suffering from a sharp attack of intermittent fever.” During the malaria attack Wallace had a breakthrough that explained the mechanism of natural selection. Within two days of the fever subsiding he had written “On the Tendency of Varieties to Depart Indefinitely from the Original Type,” sometimes called the Ternate Paper, which contained the momentous concept “the fittest would survive” which explained the mechanism of natural selection. Wallace then sent his paper to Charles Darwin, who up to that point had not published one word on evolution or natural selection. See the chapter “Ten Pages That Changed the World” to see how that worked out.

* * *

Much has been made of Ali’s nursing skills. Yet Wallace wrote that he also cared for Ali on various occasions when the young man was incapacitated by often-serious fevers. Wallace and Ali both suffered, and they helped each other overcome continuing episodes of illness, fevers, inflammations, suppurating sores, accidents, shipwrecks, and general misery, not to mention the exasperation of trying to manage a string of often-unreliable, sometimes larcenous, hired hands.

While in Coupang (today Kupang) on the island of Lombok, for example, Wallace asked his host for “a horse for Ali, who was lame.”[9] Apparently the horse never appeared, and Wallace noted:

“I gave Ali my horse, and started on foot, but he afterward mounted behind Mr. Ross’s groom, and we got home very well, though rather hot and tired.[10]

In another passage, from Makassar, Wallace wrote about his concern for Ali’s health, mixed with his annoyance at not having a regular cook.

Although this was the height of the dry season, and there was a fine wind all day, it was by no means a healthy time of year. My boy Ali had hardly been a day onshore when he was attacked by fever, which put me to great inconvenience, as at the house where I was staying nothing could be obtained but at meal-times. After having cured Ali, and with much difficulty got another servant to cook for me, I was no sooner settled at my country abode than the latter was attacked with the same disease, and, having a wife in the town, left me. Hardly was he gone than I fell ill myself, with strong intermittent fever every other day. In about a week I got over it by a liberal use of quinine, when scarcely was I on my legs than Ali again became worse than ever. His fever attacked him daily, but early in the morning he was pretty well, and then managed to cook me enough for the day. In a week I cured him.[11]

And Wallace sought medical help for Ali in Maros, north of Macassar (and again bemoaned the inconvenience).

My boy Ali was so ill with fever that I was obliged to leave him in the hospital, under the care of my friend the German doctor, and I had to make shift with two new servants utterly ignorant of everything.[12]

And again on Macassar, Ali once more came down with fever, and again Wallace was annoyed that his routine was disrupted:

My Malay boy Ali was affected with the same illness, and as he was my chief bird-skinner I got on but slowly with my collections.[13]

* * *

I wonder what we would learn by flipping things around and looking at the Wallace-Ali relationship from Ali’s point of view. What did Ali think about all those characteristics (well-educated, science-influenced, relatively wealthy, curious, much-travelled, open-minded, meticulous, willing to sacrifice comfort for the sake of the quest) that we so admire in Wallace? Can we speculate on how Ali judged his tall, gawky, bearded (beards are a constant source of fascination, and often fear, to many rural Asians) employer? At times Ali might have been confused — Wallace was his boss, but he cared for Ali when he was sick, almost as a father might have done. How did Ali try to make sense of this Englishman, who, with all the wealth and status that designation implies, deliberately chose not to live like other white foreigners but instead insisted on spending miserable weeks camped out in the forest, in palm leaf shelters that leaked, fighting rats, dogs, and ants that tried to devour his specimens. And my word, those specimens. Often they were dull in color and to Ali without interest. Yet Wallace seemed as happy to collect a miserable grey-brown beetle as tiny as a rice grain with the same enthusiasm as he collected a big, bold hornbill. And what mental illness drove Wallace to spend long periods huddled over his journal writing intently about an ant. A miserable semut! And so many of them! Wallace said they were all different, but Ali couldn’t see much beyond the fact that some were big and some were small and some were black and some were red. And Wallace smelled. Even in the forest, Ali took pride in his hygiene, washing his clothes and himself at every opportunity with buckets of rain water or in a nearby stream. But, he had to admit, some of the butterflies and birds were attractive. However, all told, if Ali was in control of the shotguns he might better have used his time and ability to shoot deer for the dinner table.

* * *

Wallace was travelling independently — he had no government or military support system. He also had little cash — he was a self-described “beetle collector” who earned enough to survive by sending natural history specimens to Samuel Stevens, his beetle agent in London, who then sold the critters to enthusiastic collectors. (Darwin, on the other hand, during his famous voyage on the HMS Beagle, lived on-board in what was, in effect, a floating base camp, with Royal Navy sailors on hand to provide security, logistics, laundry and food. He had a permanent, dry place to write his notes and mount his specimens. The downside: Darwin shared a cabin with the captain, Robert FitzRoy, who, Darwin noted, had a quick temper which resulted in behavior sometimes “bordering on insanity.”

Wallace moved camp some one hundred times during his eight years in Southeast Asia, and we can imagine that greedy local merchants saw big profits when a white man like Wallace came along to buy supplies. Ali probably reduced the amount that Wallace was over-charged, and helped in negotiations with self-important village chiefs (“Hello good sir, do you mind if I set up a camp in your forest and shoot your birds and collect your butterflies?”). Ali organized the thousands of annoying details of travel, and he hired and fired porters and laborers.

Of course Ali was just one of dozens of individuals who helped Wallace; he admitted he relied on the kindness of strangers. Cranbrook and Marshall note that Wallace “depended heavily on goodwill, but his position was enhanced by the standing he gained on the recommendations of people in authority at all levels, from Governor to local ruler or head man. His progress in the Moluccas shows that news of his presence could travel ahead of him and, apparently by custom, successive coastal villages provided rowers to take him on to the next settlement, the men sometimes swimming out to join his boat.”

* * *

After seven years travelling together throughout the Indonesian archipelago Wallace and Ali made their way to Singapore. Wallace was getting on a ship to return to England. Wallace took Ali to a photographer; the picture (the only one we have) shows a full-mouthed, serious, dark-complexioned lad with wavy hair, thick eyebrows, and a broad nose, dressed in a dark European-style jacket and under-jacket, white shirt, and a white bow tie. Wallace remembers the farewell:

On parting, besides a present in money, I gave him my two double-barrelled guns and whatever ammunition I had, with a lot of surplus stores … which made him quite rich. He here, for the first time, adopted European clothes, which did not suit him nearly so well as his native dress, and thus clad a friend took a very good photograph of him. I therefore now present his likeness to my readers as that of the best native servant I ever had, and the faithful companion of almost all my journeyings among the islands of the far East.[14]

Then what? Where did Ali go?

There are three options: Sarawak, Singapore, or Ternate.

* * *

Part of the solution to the puzzle as to where Ali “retired” depends on where he was from.

There are two opinions – he was from Sarawak or he was from outside Sarawak.

* * *

Let’s examine the first claim, that Ali was from Sarawak.

That conclusion fits in with the fact that Wallace hired Ali in Sarawak.

In an unpublished 2016 paper based largely on oral history, Kuching residents Tom McLaughlin and Suriani binti Sahari claim that Ali’s patronym was Ali bin Amit (Ali, son of Amit)[15], that he was born around 1849, was the youngest of five children, and came from Kampung Jaie, today about two hours drive from the Sarawak capital of Kuching. McLaughlin and Suriani, who have spent years speaking with Sarawak historians and residents, suggest that Ali worked in James Brooke’s household under the tutelage of his elder brother Osman, later known as Panglima Seman.

John van Wyhe, of National University of Singapore, and Gerrell M. Drawhorn, of Sacramento State University, in a 2015 article in JMBRAS, the Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, similarly say “It is likely that Ali was from the groups of Muslims living in various small villages of houses on stilts along the Sarawak River. He may also have come from the village of Santubong…. Ali was perhaps about 15 years old, dark, short of stature with black hair and brown eyes. He would have grown up on and around boats. He would have spoken the local dialect of Malay and was probably unable to read or write.”

Wallace himself, in a lecture in London in 1867, referred to Ali as “a native of Borneo.”[16]

* * *

Another view suggests Ali was not from Sarawak.

Although Wallace described Ali as “my Bornean lad,” Cranbrook and Marshall note that Sarawak has not been confirmed as Ali’s birth-place.

They offer circumstantial evidence that Ali was “a roving youth of Malay race born and raised outside Sarawak,” and “it is plausible that Ali’s ‘own country’ was Ternate, where he had grown up hearing the Dutch style of Malay, where he found his wife with surprising alacrity and where he chose to settle permanently.”

Their arguments are that “Ali’s domestic abilities (‘he was clean and could cook very well’) denote independence from his family, and possibly some previous experience as a servant. His evident capability to organise his employer’s affairs, with a level of command over other men, implies maturity and self-reliance. Ali’s language, his skills and his self-confident authority are wholly inconsistent with the image of an unsophisticated Sarawak lad…. Ali’s prowess as a boatman could have been gained through serving on inter-island voyages.”

Cranbrook and Marshall offer another argument that Ali wasn’t from Sarawak. They note that in one passage Wallace, recalling an 1858 stay on Aru, quotes Ali; this is the only time we hear a direct quote attributed to the young man. Wallace wrote that he and Ali were staying in a house containing “about four or five families & there are generally from 6 to a dozen visitors besides. They keep up a continual row from morning to night, talking laughing shouting without intermission…. My boy Ali says ‘Banyak quot bitchara orang Arru’ [roughly The Aru people are very strong talkers] having never been accustomed to such eloquence either in his own or any other Malay country we have visited.” Cranbrook and Marshall say that the phrase “is far from the vernacular of Sarawak Malay and shows that, early in his employment, Ali addressed [Wallace] in the Bazaar Malay typical of the area of Dutch control.”[17]

* * *

Just to review.

We know Wallace hired Ali in Sarawak.

We think, but aren’t certain, that Ali came from Sarawak.

That leaves the biggest question. After saying goodbye to Wallace did Ali “retire” to Sarawak, Singapore, or Ternate?

* * *

The only accurate answer to that last question — where did Ali go to “retire” — is that we aren’t sure. Different people have different opinions about everything. People then and now seem to arrive at conclusions in one of two ways. They might have an opinion and then seek evidence to support their views (for instance, people who espouse creationism and use Biblical references and circular logic as their proof). Or they might examine data and come to a conclusion based on statistics, logical arguments, and replicable experiments (for example, people who believe in climate change because the science is, in their minds, sufficiently convincing). But usually we make our decisions based on a combination of what we want to be true, combined with a dose of hard evidence. The balance between the two extremes varies depending on our personalities, education level, and social environment. Consider how we judge a politician running for elected office. Do we believe the countless stories circulating about her? What news stories do we believe? What rumors do we believe? For example, do we believe, in our hearts, that President Barack Obama was born in Kenya in spite of hard evidence he was born in Hawaii? Do we believe that U.S. astronauts really landed on the moon or are we convinced the 1969 moon landing was a hoax produced in a top secret TV studio in Nevada? What is the tipping point that causes our support (or disapproval) to flip? So it is with the search for Ali’s retirement home. We have ideas, we have snippets of evidence, a bunch of clues and a jumble of hunches. But we don’t have a smoking gun. Or do we? We’re not certain. The search goes on.

* * *

In Sarawak today, people have a modest awareness of Wallace, and almost zero awareness of Ali.

Among the few people in Kuching who care about the Ali saga is Tom McLaughlin, an American historian, and his Sarawak-born wife Suriani binti Sahari.

McLaughlin and Suriani base most of their case on interviews with elders (including one prominent bomoh, or Malay shaman) living in Malay kampungs around Kuching. McLaughlin and Suriani believe that following his Singapore farewell to Wallace Ali returned to Sarawak. They say “he built a 20 post house on stilts at Kampung Jaie.… He became involved in processing of palm sugar … he smoked palm cigarettes and loved coffee … [he purchased] sweets for the children [and walked] with a cane.”

McLaughlin and Suriani were told Ali had a black sea chest of British origin, which they say contained a “picture of Ali with a European gentleman [and] papers with British seals.” The box was evidently haunted because it “became alive each Friday night making noises. Because of the belief in ghosts, the box was taken out and placed in the sea.”

For several months in 1869 Ali seemingly disappeared from Wallace’s chronicle. Some observers call this Wallace’s Gap Year; I call it his Agatha Christie period. McLaughlin and Suriani believe Ali “probably returned to Kampung Jaie with money and to check on his nephews” and to return for the Hari Raya (Eid) celebrations.

McLaughlin and Suriani also state, according to oral history, that after returning to Sarawak he married a woman named Saaidah binti Jaludin. (I asked McLaughlin to explain the contradiction of Ali having a Sarawak wife, since Wallace twice mentions that Ali married in Ternate — see below. McLaughlin suggested that I was looking at the situation with an overly Western perspective in which monogamy is the norm, and noted that polygamy was permitted both by Islamic Shariah law as well as by adat, the traditional culture and value system to which Ali would have adhered. Also, according to McLaughlin, Ali had made a promise to look after the children of his brother Panglima Osman (Seman), and familial responsibility in Sarawak overcame the obligation of his marriage in Ternate.)

And McLaughlin and Suriani quote a long pantun (a traditional, often chanted, Malay oral narrative), sung to them by Jompot bin Chong, the grandson of Panglima Osman (Seman) who was Ali’s elder brother. Verses include statements like these (in translation from Sarawak Malay): “How are you, Wallace the white man/Wallace and brother Ali are good friends/Unfortunately this year our team work has ended.” McLaughlin told me that he was sceptical himself with the “bomoh’s observations until Jompot came up with the pantun. He didn’t even have to think about it … just spouted it out. Then I checked with an 86-year-old ‘pantun expert’ here in Kuching and she said she had heard of it. The pantun, in itself, is very strong evidence that Ali was here.”

And finally, they were told that “[Ali] died just after the Japanese invaded Kuching,” which would have made Ali about a hundred years old at the time of his death. They visited what they were told was Ali’s grave in Kampung Jaie.

* * *

Perhaps Ali stayed in Singapore? I put the question to various Malay historians in Singapore and was greeted with polite interest and zero desire to follow-up. There is no evidence, and no one suggests, that Ali stayed in Singapore; I think we can discount this possibility.

* * *

That leaves Ternate, the town where Wallace had his eastern Indonesia base camp for some three-and-a-half years. Wallace and Ali spent long periods there, recovering from voyages to distant islands and preparing for their next adventure. Wallace wrote fondly about the creature comforts he enjoyed in Ternate — “a deep well supplied me with “pure cold water … luxuries of milk and fresh bread … fish and eggs … ample space for unpacking, sorting, and arranging my treasures … delightful walks.”[18]

* * *

There are several morsels of evidence that Ali settled in Ternate.

First, and perhaps most importantly, Wallace twice refers to Ali’s having married and established a family in Ternate; Wallace refers to Ali’s marriage in a letter to Samuel Stevens from Ceram on November 26, 1859:

[My] best [man, referring to Ali] is married in Ternate, and his wife would not let him go [with Wallace to Ceram]; he, however, remains working for me and is going again to the eastern part of Gilolo. [italics Wallace] [19]

Many years later, in his autobiography, Wallace again refers to Ali’s marriage and suggests that Ali’s wife had loosened her grip on her husband’s travels.

During our residence at Ternate he married [probably in early 1859], but his wife lived with her family, and it made no difference in his accompanying me whenever I went till we reached Singapore on my way home. [20]

Earl of Cranbrook, a leading ornithologist, mammalogist, and historian, and Adrian G. Marshall, historian and author, agree that Ali returned to Ternate, stating unequivocally “After ARW [Alfred Russel Wallace] departed from Singapore, Ali returned to Ternate to rejoin his wife and, perhaps, a young family.”

And there is a third stream of evidence that Ali settled in Ternate.

In 1907 American naturalist Thomas Barbour visited Ternate and claimed he met Ali, who was by then an old man.

Three times Barbour mentions meeting Ali.

In 1912 Barbour, director of the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University, wrote in a scientific paper: “I showed a Ceram specimen of L. muelleri to many intelligent natives of Ternate, including indeed Ali, the faithful companion of Wallace during his many journeys, now an old man [Ali would have been around 70 years old], and all agreed that they had not seen such a lizard before.”

In 1921, in another scientific paper, Barbour wrote: “On the day of my walk to the Ternate lake an old Malay spoke to me; he had long forgotten his English, but he tapped his chest, drew himself up and told me he was Ali Wallace. No lover of ‘The Malay Archipelago’ but remembers Ali who was Wallace’s young companion on many a hazardous journey. After my return a letter from Mr. Wallace speaks of his envy of my having so recently met his old associate.”

And in his autobiography of 1943, Naturalist at Large, Barbour wrote the most detailed account: “Here came a real thrill, for I was stopped in the street [in Ternate] one day as my wife and I were preparing to climb up to the Crater Lake. With us were Ah Woo with his butterfly net, Indit and Bandoung, our well-trained Javanese collectors, with shotguns, cloth bags, and a vasculum for carrying the birds. We were stopped by a wizened old Malay man. I can see him now, with a faded blue fez on his head. He said, ‘I am Ali Wallace.’[21] I knew at once that there stood before me Wallace’s faithful companion of many years, the boy who not only helped him collect but nursed him when he was sick. We took his photograph and sent it to Wallace when we got home. He wrote me a delightful letter acknowledging it and reminiscing over the time when Ali had saved his life, nursing him through a terrific attack of malaria. This letter I have managed to lose, to my eternal chagrin.”[22]

* * *

With this evidence that Ali had settled in Ternate I went to the island and spoke to the mayor and various officials to encourage them to find Ali’s descendants. After leaving Wallace in Singapore Ali would have returned to Ternate as an important and relatively wealthy man. He had travelled widely, and been friends with a tall, somewhat quirky Englishman. He had his photo taken wearing European clothes. He had tales to tell. Wallace recalled that while in Singapore Ali had “seen a live tiger [and] made much of his knowledge when we reached the Moluccas, where such animals are totally unknown. I used to overhear him of an evening, recounting strange adventures with tigers, which he said had happened to himself. He declared that these tigers were men who had been great magicians and who changed themselves into tigers to eat their enemies…. These tales were accepted as literal facts by his hearers, and listened to with breathless attention and awe.[23]

People, especially family members, would have heard his stories and repeated them as part of family history.

I suggested to Ternate government officials, royal family members, journalists, and academics that they could place an article in the local paper; I even volunteered to write it. “Let’s show Ali’s photo and story to the village elders,” I suggested. “Let’s get a university student to write a thesis on the search for Ali.” I pointed out that this search could generate national, even international news, and be a stimulus for the tourist business and a catalyst for conservation. It would certainly help build local pride, which is always a good thing for elected officials to bask in. Bagus, everyone said. Good idea. Lots of enthusiasm, no action. Indonesian inertia? A dearth of intellectual curiosity? A reluctance to pursue a “foreign” idea?

In a fit of frustration I went on what I knew would be Quixotic quest. Surely, I thought, someone would have a memory of great-great granduncle Ali.

With the help of a friend who spoke the local dialect, I strolled through the Malay kampung, showed the photo to every old person I met and asked if they had heard of this guy Ali.

I gave lectures to history and biology students at universities in Ternate and neighboring cities and encouraged them to seek Ali. A few students I spoke with privately expressed polite interest, but quickly zoned out when I explained that for their research they would have to speak with old folks in the villages, and go through dusty records. “But that sounds like … field work!” they would explain, before politely excusing themselves.

* * *

It seems as if Ali is destined to remain an enigma, a lost soul in the large filing cabinet labeled: People Who Did Important Things But Never Got Any Credit. I suspect we all have a bunch of Alis in our memory banks and karmic stockpiles, folks who have helped us in innumerable ways, folks to whom we rarely raise a glass. We don’t know Ali’s birthday. But perhaps we might declare January 8, Wallace’s birthday, as Global Ali Day, to give remembrance to those who nursed us, did us unexpected favors, who, sometimes, without our awareness, eased our paths.

[1] My Life, Vol. 1, 382.

[2] Ibid., 383.

[3] The Malay Archipelago, 335–6.

[4] It might more accurately have been named “Ali’s Standard-wing/Semioptera alii.”

[5] The Malay Archipelago, 412.

[6] Ibid., 484.

[7] The Malay Archipelago, 394.

[8] Ibid., 388, 390

[9] Ibid., 177.

[10] Ibid., 178.

[11] Ibid., 222.

[12] Ibid., 236.

[13] Ibid., 348.

[14] My Life, Vol. 1, 383.

[15] Wallace never indicated Ali’s patronym.

[16] “On the Races of Man in the Malay Archipelago.” Lecture, 1867.

[17] I have problems with the conclusion that the “Banyak quot bitchara orang Arru” quote indicates Ali was not from Sarawak. First, the incident occurred after Ali had been with Wallace for two years; plenty of time for him to have become accustomed to speaking “standard” Malay. Second, Wallace was recalling a relatively unimportant conversation and there is no reason to think that Wallace would have either remembered it accurately (can you remember verbatim a mundane conversation you had just yesterday?). Third, Wallace provided the essential meaning of Ali’s statement, using the basic Malay that would be recognizable to any reader familiar with the region. Writers “approximate” all the time. I don’t place too much credence that this particular piece of evidence answers the questions about Ali’s origin.

[18] The Malay Archipelago, 314.

[19] Letter to Samuel Stevens, Nov. 26, 1859.

[20] My Life, Vol. 1., 383..

[21] Some critics take issue with this quote, arguing that Ali might have more understandably addressed Barbour in Dutch or Malay. From my point of view there are several valid explanations. Undoubtedly Ali would have learned a bit of English while with Wallace, and he was dredging out his limited English vocabulary to impress foreign visitors. Perhaps Ali did address Barbour in Dutch or Malay, and Barbour simply gave readers the English translation. And as for Ali referring to himself as Ali Wallace, well that makes perfect sense, since Malays don’t use family names but refer to themselves as the son or daughter of so-and-so. Why wouldn’t Ali consider himself Wallace’s son, or at least an adopted son? Perhaps the encounter was not even as theatrical as Barbour claims; he might have dramatized it for the sake of his narrative. But it might well have occurred as reported since we know Ali was a bit of a showman, as evidenced by Wallace’s recollection of Ali telling tall tales to colleagues. And it is unlikely anyone except Ali would have had a serious discussion with a foreign collector about an obscure lizard. For me there is no reason to doubt Barbour’s sincerity in reporting meeting Ali.

[22] It would have been nice if Wallace had also written a note to Ali.

[23] “On the Races of Man in the Malay Archipelago.” Lecture, 1867.