Shooting Orangutans and Pondering the Universe

Posted on 25. Jun, 2010 by Paul Sochaczewski in Alfred Russel Wallace and his assistant Ali, Articles

Alfred Russel Wallace spent 18 lonely months in Sarawak, writing the precursor to his theory of evolution.

SANTUBONG, Sarawak, Malaysia

Different people react to solitude in different ways.

Some people converse with demons and angels. Some folks become truly, giggling-at-midnight mad. Some find enlightenment. And once in a while a guy who spends too many rainy nights in a leaky hut will change the course of history.

One hundred and fifty years ago, on a quiet beach on the west coast of Borneo, a young British naturalist named Alfred Russel Wallace made an intellectual breakthrough that would lead two years later to his developing the theory of natural selection, the basis for the theory of evolution.

Wallace, with the benefit of a grant from the Royal Geographic Society, was just beginning his epic eight-year (1854-1862), 22,400 km journey through Southeast Asia. This voyage, which he wrote about in his classic book The Malay Archipelago, netted him 125,660 specimens, including some 900 new species of beetles, 200 new species of ants, 50 new species of butterflies, and 212 new species of birds. Besides his breakthroughs on evolutionary theory, during the journey he developed the concept that later became known as the Wallace Line, explaining how changing sea levels had alternatively isolated and united land masses, resulting in sometimes startling differences between the wildlife of neighboring islands.

Wallace’s benefactor in Sarawak was James Brooke, popularly called the “White Rajah of Borneo”. They met in London in early 1853, and subsequently Brooke wrote to Wallace that he would be very glad to see him in Sarawak. The two men later met up in Singapore in September 1854 during the Commission of Inquiry into Brooke’s handling of piracy. Brooke again offered the young Englishman “every assistance” if he visited Sarawak. Wallace arrived in Sarawak (both the territory and the city now known as Kuching were then referred to as Sarawak; Sarawak itself today is a state of Malaysia) on November 1, 1854.

Wallace spent a productive 14 months in Sarawak, netting and pinning 1,500 species of butterflies and 2,000 species of beetles, over 1,000 of them in less than a single square mile. Within one busy fortnight he averaged 24 new beetle species every day. “During my whole 12 years collecting in the western and eastern tropics, I never enjoyed such advantages,” he wrote.

Wallace was alone much of the time, and used his isolation to ask some of the most basic questions – why are there so many varieties of life on earth, and why are they found where they are? Do creatures evolve? And if so, where do humans fit into the scheme of things?

At the time, Victorian-era intellectuals were hard at work debating these questions, but until 1855 precious few of them had come up with anything more useful than brandy-after-dinner speculation. Then the relatively unknown Wallace came up with a key step. Wallace’s breakthrough came about after weeks of lonely vigils in jungle camps, leaky hilltop retreats, and in the relative luxury of watching the monsoon rain while residing at Rajah Brooke’s beachfront bungalow in Santubong on the Sarawak coast.

* * * * *

Several years ago I went to Santubong to look for the site of the White Rajah’s bungalow. Nobody in the village had any idea where the house might have been located, but, using a bit of admittedly fuzzy logic to find the site I figured that Brooke would have ordered his bungalow built with a fine view and open to sea breezes. Continuing the logic, I imagined that subsequent British governors would have built their bungalows and official rest houses on the same spot as James Brooke’s cottage.

I finally found the place – an abandoned villa, maybe 50 years old, sitting on a small rise and surrounded by housing for government staff. The remains of the old British rest house were more suited for an Asian horror movie than a relaxing seaside vacation. The building’s roof had caved in, the floors had collapsed, and spiders and bats roamed freely.

I was disturbed. This site should be a museum, not a hovel. It was here, in February 1855, that Wallace wrote what later became known as the Sarawak Law, a short scientific paper that set the stage for the theory of natural selection that he wrote three years later while in Ternate, in eastern Indonesia.

Although the Sarawak Law seems simplistic today, at the time it was considered a major (and courageous) step towards understanding the question of whether species changed, and if they did, how. Wallace wrote: “Every species has come into existence coincident both in space and time with a pre-existing closely allied species.” Put another way, new species don’t just fall from they sky, they have a causal link with something that existed previously.

I continued to tour the dilapidated beachfront house in Santubong, wiped the cobwebs off my face and imagined Wallace relaxing on the verandah, discussing his ideas with a skeptical Brooke and an even more disbelieving Spencer St. John, Brooke’s secretary, who wrote “We had at this time…Mr. Alfred Wallace, who was then elaborating in his mind the theory…of the origin of species…if he would not convince us that our ugly neighbors, the orangutans, were our ancestors, he pleased, instructed, and delighted us by his clever and inexhaustible flow of talk – really good talk.”

* * * * * *

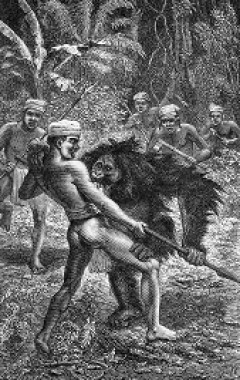

Orangutans were a key reason British explorer, naturalist and beetle-collector Alfred Russel Wallace came to Asia between 1854-1862. “One of my chief objects in coming to stay at Simunjon [in Sarawak] was to see the orang-utan (or great man-like ape of Borneo) in his native haunts, to study his habits, and obtain good specimens,” Wallace wrote.

Wallace was successful in obtaining “good specimens”. He famously shot 17 of the red apes to obtain skins and skeletons that were sold to British collectors via his London-based “beetle agent”, proudly noting that the South Kensington Museum offered “one hundred pounds in gold for an adult male [orangutan] skin and skeleton.” Big money for a penniless explorer whose only source of income was the revenue earned from the sale of “natural productions” that he collected.

* * * * *

While charismatic megavertebrates like the orangutans were obvious financial treasures for Wallace, his bread and butter came from beetles and butterflies, moths and ants, birds and curiosities like flying squirrels.

Wallace found the moth-collecting exceptionally productive in the vicinity of Brooke’s small bungalow in the hills of Peninjau, an hour outside the charming state capital Kuching.

Some thirteen years ago I intended to visit the site but wanted some knowledgeable company. Traveler’s serendipity blessed me as I explained my interest in Wallace to a lady who ran one of the many antique shops along Kuching’s riverside. “You should meet Uncle Ho” she said. “He would know about Peninjau.” Some ten minutes later, almost on cue, “Uncle Ho” – Ho An Chon, one of Sarawak’s leading historians, wandered into the shop. I asked how they knew each other and the lady explained that she was the daughter of the first Sarawak chief minister, and Uncle Ho had been one of her father’s close friends.

My good luck was to continue. I arrived at the neat village at the base of the steep hill, and we stopped at a house to ask directions. The man who answered the door was Stephen Senyium, an old school friend of Uncle Ho’s whom he hadn’t seen for decades; Senyium then guided us to the summit.

Using Wallace’s notes: “a cool spring under an overhanging rock…huge boulders as big as houses,” we climbed the “steep pyramidal mountain…covered with luxuriant forest,” and found the site of the long-abandoned “rude wooden lodge where the English Rajah was accustomed to go for relaxation and cool fresh air.” Of course the structure was gone but surprisingly, the belian ironwood supports were still partially intact, some 150 years after the lodge had been built.

Wallace, alone for much of the time, found it the best spot in Asia for capturing moths, some 1,386 of them over 26 nights. “I placed my lamp on a table against the wall,” he wrote, “and with pins, insect-forceps, net, and collecting-boxes by my side, sat down with a book…on good nights I was able to capture from a hundred to two hundred and fifty moths…some of them would settle on the wall, some on the table, while many would fly up to the roof and give me a chase all over the veranda before I could secure them.”

No doubt during the lonely rainy nights he had ample time to think about evolution.

* * * * *

This year I found that a minor evolution in Wallace awareness has taken place in Sarawak.

I went back to Sarawak for the 2005 Rainforest World Music Festival, a joyful event held each year in the Sarawak Cultural Village in Santubong. Several days later, I presented a paper at an international conference in Kuching called “Wallace in Sarawak – 150 Years Later”. I was thrilled that academics in Sarawak wanted to recognize Wallace’s contribution to science. The meeting was opened by Sarawak Chief Minister Taib Mahmud, who encouraged the local university to “set up a Wallace Centre at Santubong where we can showcase his pioneering works [in order to inspire] our young scientists.” It was an impassioned speech from a man not generally considered a friend of nature, referring to Wallace’s ideas as an “important piece of history of relevance to modern policy makers,” and noting how Wallace “rose above his station in life through sheer personal efforts and never-give-up attitude.” Referring to the important role that his state played in developing Wallace’s thoughts, Taib Mahmud added that “Sarawak became for Wallace what Galapagos was for Darwin.”

As one of the conference participants, I returned to Santubong, to visit the site of Rajah Brooke’s bungalow, where I had cleared cobwebs and chased bats several years earlier.

I was surprised to see that signboards had been constructed directing traffic to “Wallace Point”, and I arrived to find that the 1950s-era government bungalow on the Brooke site had been dramatically cleaned and spruced up. While the well-educated executives of the Sarawak Economic Development Corporation, which is responsible for the site, were on a steep learning curve about why all the fuss was going on, there was no shortage of big ideas floating around concerning what should be done with the hillside retreat. I proposed a “living museum”, which would highlight Sarawak’s biodiversity but also showcase how Wallace captured and identified beetles, how he stuffed birds, and what he did to prevent tropical insects and rats from eating his hard-earned “natural productions”. The Earl of Cranbrooke, who wrote Mammals of Borneo among other seminal works, had another, perhaps better, idea. He suggested that the site should be developed as a refuge from modern stress, proposing the creation of a “Wallace Center for Contemplation and Original Thought.”

Neither of these grandiose ideas have been implemented [but in 2008 Sarawak officials designated nearby Santubong Mountain as a national park]. After this initial burst of enthusiasm there has been little progress to either develop the historic site or recognize Wallace’s achievements in Sarawak and encourage Malaysian researchers to pursue new scientific frontiers. The site remains empty, populated perhaps by lonely ghosts and the memories of big lonely ideas.

[David Spencer Hallmark co-authored one version of this article]