Bruno and the Blowpipes

Posted on 25. Jun, 2010 by Paul Sochaczewski in Articles, Environment

Who will determine the future of Sarawak’s isolated Penan?

BAREO, Sarawak, Malaysia

Bruno Manser has disappeared in Borneo and is feared dead.

Manser, 47, was last seen in May 2000 in the isolated village of Bareo in the Malaysian state of Sarawak, close to the border with Indonesia. The Swiss had illegally entered Sarawak to rejoin his tribal friends the Penan, with whom Manser had spent some six years fighting the timber operators that natives claim are destroying their forest home.

I’ve met Manser several times. We are not close, but I respect his understanding of the realpolitik that is at the heart of most fights between native peoples and paternalistic governments.

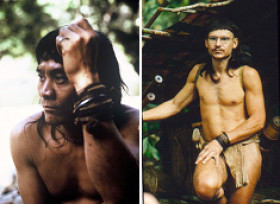

He achieved worldwide recognition from 1984-1990 when he lived in the rainforest with the semi-nomadic Penan of Sarawak. Malaysian officials saw him as a fugitive and a provacateur and called him an “enemy of the state number one.” Manser constantly avoided arrest with the panache of a Swiss Robin Hood, zigging and zagging through the forest when police were on his trail, even once escaping after he had been captured. When he left Sarawak, through Brunei, he returned to Switzerland to create the non-profit Bruno Manser Foundation. In 1999 he returned to Sarawak and in a made-for-media stunt paraglided onto the front lawn of Sarawak Chief Minister Tan Sri Abdul Taib Mahmud. Bruno Manser, like other campaigners, say ultimate responsibility for the poor treatment the state’s indigenous people receive is due to Taib Mahmud’s attitudes and links to timber companies. Bruno Manser offered Taib Mahmud a truce in exchange for the government creating a biosphere reserve for the Penan. The Swiss man with the impish grin and John Lennon glasses was quickly deported.

Manser has arguably been the most potent catalyst for media coverage of the fight by the Penan, and other Sarawak natives, to protect their forests against what they say are insensitive governments and greedy timber barons.

Defensive Sarawak government officials note that 95% of the state’s substantial oil revenue goes to federal coffers, leaving Sarawak little choice but to earn money from natural products, of which timber is by far the most profitable. “Where are we to get money except through the forest,” asks Dato James Wong, former Sarawak Minister of Tourism and Local Government and one of the state’s leading timber concessionaires.

Malaysia is the world’s leading exporter, by far, of tropical logs, tropical sawn wood, and tropical veneer, and second, after Indonesia, a far larger country, of tropical plywood.

According to Bruno Manser Foundation, more than 70% of Sarawak’s rainforest has been cut during the past 20 years. Today Malaysian companies run timber operations and plywood mills as far afield as Guyana, Suriname, Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands according to a report by Nigel Sizer of World Resources Institute and Dominiek Plouvier, an independent forestry consultant.

I served in the United States Peace Corps in Sarawak, not too far from where Manser has disappeared. For my job (and pleasure) I travelled to isolated longhouses, occasionally running into Penan, who appeared like a breath of wind, shared some food, gratefully accepted some tobacco or salt, and then went about their business.

During those admittedly idyllic days in the late 1960s we would throw a circular fishing net into rivers and come up with more than enough fish for dinner. We would go out at night to hunt wild boar and more often than not return with a hairy pig on our shoulders. The rivers were clean, and jungle gibbons hooted their morning call behind the longhouses.

On subsequent trips back to Sarawak I was angry by the desolation of the landscape by timber operators, and heard complaints from dozens of people in dozens of longhouses. Their homes were being destroyed and they weren’t getting anything for it. Fishing and hunting was terrible. The rivers were dangerous places, muddy and filled with debris from timber operations. I visited Penans who had been resettled into government-built longhouses, ugly structures with standard government issue architecture similar to army barracks or timber camp housing. Tin roofs amplified the heat, making the residences uninhabitable during the day. The Penan I saw were listless, with vacant eyes. True, they now had access to basic health care and simple schools, but it seemed as if all the energy had been sucked from their thin frames.

When I discussed these issues with Malaysian officials I got a common defensive response, basically, “don’t tell us what to do, we know what’s best for the Penan and the forests.”

“Look at this map,” notes Chris Elliott, director of the WWF-World Wide Fund for Nature Forests for Life Campaign. He points to an amorphous shaped illustration published in the Bruno Manser Foundation newsletter that indicates the territory of nomadic Penan and remaining virgin forest in Sarawak. “The foreigners were telling the people in Sarawak what to do and how to do it,” Elliott said. “Bruno backed the Sarawak authorities into a corner by telling them what they should do. Even the slightest whiff of Western lecturing will put them on the defensive,” he adds, noting that you’ll find similar conflicts and reactions in places like British Columbia in Canada, parts of Australia, Indonesia and Brazil.

Perhaps it was a sloppy tactic – using western style confrontation to get policy changes in an Asian country.

Certainly, Malaysian officials resent being told what to do by pesky foreigners.

During the height of Manser’s long Sarawak escapade in the 1980s, Malaysia’s Prime Minister Mahathir bin Mohamed had this testy exchange of correspondence with young Darrell Abercrombie from Surrey, England.

Using his best penmanship, the boy wrote:

“I am 10 years old and when I am older I hope to study animals in the tropical rain forests. But if you let the lumber companys [sic] carry on there will not be any left. And millions of Animals will die. Do you think that is right just so one rich man gets another million pounds or more. I think it is disgraceful.”

The Prime Minister replied on August 15, 1987:

“Dear Darrell, It is disgraceful that you should be used by adults for the purpose of trying to shame us because of our extraction of timber from our forests.

“For the information of the adults who use you I would like to say that it is not a question of one rich man making a million pounds.…

“The timber industry helps hundreds of thousands of poor people in Malaysia. Are they supposed to remain poor because you want to study tropical animals?….

“When the British ruled Malaysia they burnt millions of acres of Malaysian forests so that they could plant rubber…. Millions of animals died because of the burning. Malaysians got nothing from the felling of the timber. In addition when the rubber was sold practically all the profit was taken to England. What your father’s fathers did was indeed disgraceful.

“If you don’t want us to cut down our forests, tell your father to tell the rich countries like Britain to pay more for the timber they buy from us….

“If you are really interested in tropical animals, we have huge National Parks where nobody is allowed to fell trees or kill animals….

“I hope you will tell the adults who made use of you to learn all the facts. They should not be too arrogant and think they know how best to run a country. They should expel all the people living in the British countryside and allow secondary forests to grow and fill these new forests with wolves and bears etc. so you can study them before studying tropical animals.

“I believe strongly that children should learn all about animals and love them. But adults should not teach children to be rude to their elders.”

I believe strongly that children should learn all about animals and love them. But adults should not teach children to be rude to their elders.”

* * *

The other common response is that “we’re resettling the Penan for their own good.”

I asked Alfred Jabu, an Iban who is deputy chief minister of the Malaysian state of Sarawak, and who is a member of the indigenous Iban tribe, numerically the largest population group in the state, why he was so concerned about changing Penan lifestyles. He answered: “To give them the chance to enjoy the same benefits other Malaysians have.”

This humorless refrain is repeated whenever you talk to someone involved in resettling their less fortunate (and always more isolated) brethren. “We want to help them enjoy the fruits of our development.”

A government report admitted that “In trying to bring development to the Penans, the state government realises that the Penans are a simple people and that an overnight change is not possible. Although the government has been generous in providing the Penans with facilities and services, care has also been taken to ensure that the Penans will not be overdependent on the government so that they will not expect handouts all the time….Penans will be trained to stand on their own and learn to face the challenges of modern living like other Malaysians.”

Alfred Jabu added the final proof that the Penan are happy. “They have a Penan elder as spokesman. He lives in a big house and drives a Mercedes.”

* * *

What might have happened to Manser?

Perhaps the Malaysian security forces finally caught Manser and left him for compost in the rainforest. That way the authorities would have saved themselves an embarrassingly visible deportation or trial.

Another possibility, which I hope is the case, is that Manser has gone walkabout and is hanging out with his Penan buddies. Perhaps he got bored with Switzerland, perhaps he felt that he could do more for their cause by advising them close up. Perhaps he is planning a large media coup.

But Newsweek has reported that four Penan-led search parties have not turned up any traces of Manser, and John Kuenzli, secretary of the Bruno Manser Foundation, says, “We are resigned that if Bruno Manser were still alive, he would have been found.” Perhaps Bruno’s fate is destined to become an unsolved Asian mystery, like the 1967 disappearance of Thai silk entrepreneur Jim Thompson in Malaysia’s Cameroon Highlands or Michael Rockefeller’s disappearance in the Asmat region of New Guinea.

* * *

And what will happen to the approximately 9,000 Penan, of whom about 300 are jungle wanderers?

Certainly change is inevitable for the Penan and the thousands of other, generally more sophisticated, indigenous people of Sarawak..

Who has the blueprint for that change?

Several years ago I consulted James Wong Kim Min. Dato James was concurrently the Sarawak State Minister of Tourism and Local Government and one of the state’s biggest timber tycoons.

James Wong loved to talk with foreigners about the Penan, whom the foreign press has idealized as a group of innocent, down-trodden, blowpipe wielding, loin-clothed people who are wise in the ways of the forest but hopelessly naive when faced with modern Malaysian politics.

“I met with Bruno’s Penans in the upper Limbang [River],” he said. “I asked the Penan who will help you if you’re sick? Bruno?” Here Wong laughed. “The Penans now realize they’ve been exploited. I tell them the government is there to help them. But I ask them how can I see you if you’ve blocked the road that I’ve built for you?”

I asked if he had a message for his critics.

“If [the west] can do as well as we have done and enjoy life as much as we do then they can criticize us. We run a model nation. We have twenty-five races and many different religions living side by side without killing each other. Compare that to Bosnia or Ireland. We’ve achieved a form of Nirwana, a utopia.”

I explained my experience with Penan who had been encouraged by generous government incentives to resettle into longhouses. How their natural environment had been hammered, how their faces were devoid of spirit and energy, how they had seemingly tumbled even further down the Sarawak social totem pole.

In reply, Wong lectured me, as I have been lectured by numerous Asian officials when I raised similar concerns. In effect, he said “We just want our cousins the naked Penan to enjoy the same benefits we civilized folk enjoy.”

We are very unfairly criticized by the west,” Wong added. “As early as 1980 I was concerned about the future of the Penans.” He read me a poem he had written:

“O Penan – Jungle wanderers of the Tree

What would the future hold for thee?….

Perhaps to us you may appear deprived and poor

But can Civilization offer anything better?….

And yet could Society in good conscience

View your plight with detached indifference

Especially now we are an independent Nation

Yet not lift a helping hand to our fellow brethren?

Instead allow him to subsist in Blowpipes and clothed in Chawats [loincloths]

An anthropological curiosity of Nature and Art?

Alas, ultimately your fate is your own decision

Remain as you are – or cross the Rubicon!”

* * *

Has Manser be successful?

From a public awareness point of view he has certainly directed considerable media attention to the plight of the Penan and other tribal groups.

But he failed at his major objective: getting the Malaysian government to declare a biosphere reserve to protect the Penan and their forest. In an article in the newsletter of the Bruno Manser Foundation, the activist admitted, “success in Sarawak is less than zero.”

Chris Elliott, a WWF executive who met Manser several times, agrees that the future isn’t bright for the Penan and their forest home. “There is severe pressure from unsustainable logging, forest fires and conversion to plantations,” he says.

Manser had a cautious relationship with the conservation mainstream. No doubt he felt that groups like WWF were too soft.

”We differ on the means,” Elliott says. “WWF tried to work in partnership with the government and had some success – a few protected areas were established, there was training of staff, and new wildlife legislation was created. But neither Bruno nor WWF succeeded in getting the authorities to create a biosphere reserve, Elliott notes, adding that WWF now has little activity in Sarawak.

Nevertheless, history isn’t written by people who follow the rules. Manser sensed a major injustice and challenged the status quo in which his friends the Penan were paternalistically treated as the bottom of the Sarawak social totem pole.

So, how will the Swiss be judged by history? As an obstinate fighter for a lost cause or a romantic visionary for a victorious change in policy?

What motivated this man from rich Switzerland to live six years in the forest of Borneo with virtually nothing that most people would consider essential? He learned to process food from the starchy sago palm, learned to hunt with a blowpipe, learned how to live a life that was simultaneously ridiculously hard and unimaginably rewarding.

Manser wrote of his epiphany: “It happened in a prison in Lucerne. I was imprisoned there for three months because I had refused to learn how to shoot at human beings. One day I suddenly perceived the space inside the four walls of my cell…how my body acted as a biosphere…to be so small and yet so incredibly rich and important…I flew out of the prison, over to my parents in Basel, to my friends in Amsterdam…I flew on and left our solar system. Then I turned around and flew back. There I sat, back in my body. Since then I carry this certainty in me: everyone of us is nothing and simultaneously the most important creature in its space and place. Indispensable from the first to the last breath. So when people say: ‘don’t be active, it’s just a waste of time, it won’t help anyway’, then you already know that they’re scared of losing profit and would even sell their own grandmother. Does it have to be the children today who day say out loud to the politicians and the economists: support what is real and true, avoid what is bad!”